There's a special silence that settles over the Campagnatico hills when evening falls gently, turning the threshed fields ochre and the olive trees copper. It's a silence that speaks, full of ancient memories, of stories that the earth preserves like precious relics in its deepest layers.

Here, where the cypress trees line up like sentinels of time and the white roads wind between stone farmhouses, a man whose name still echoes through the centuries lived and died: Omberto Aldobrandeschi, son of William the Great Tuscan, knight of that powerful lineage that dominated the medieval Maremma as princes of their own land.

The Princes of Maremma

The Aldobrandeschi were not mere feudal lords. They were Counts Palatine, a dignity equivalent to that of a prince, with almost regal rights: the power to mint coins, administer justice, and command armies. Saint Peter Damian claimed that the lineage was so powerful that it possessed a castle for every day of the year.

Their origins are lost in the mists of Lombard times, when an imperial vassal named Eriprando served at the Carolingian court. From him descended Ildebrandino II, the first Count of Roselle, invested in 857 by Emperor Louis II. From that root grew the tree of a lineage that for centuries would make the Maremma its kingdom.

Omberto was the son of William I, known as the Great Tuscan—the same great Tuscan celebrated by Dante in Purgatory. His father had heroically defended Sovana in 1240 against imperial troops. His brother, William II, was a Knight Templar monk. Another brother, Hildebrandin the Red, would become the first Count of Pitigliano.

In Omberto's veins flowed the "ancient blood" of which Dante speaks, the blood of those who had carried the red cross to the Holy Land, of those who had made great donations to the Knights Templar. The Aldobrandeschi protected the Templars, and many of them had embraced the Sacred Militia, following those chivalric teachings that demanded pride, courage, and the defense of tradition and justice.

The art of chivalry and the affront to Siena

The Aldobrandeschi of Sovana and Pitigliano—Omberto's branch—lived according to ancient chivalry, where the armed knight was a proud and haughty representative of feudal nobility. Terrible were the penalties for those who failed to defend their lands and vassals: a mark of shame that stained the entire lineage.

It was 1256. Ambassadors from the Republic of Siena traversed the Maremma with the arrogant confidence that only the power of a rising city-state can inspire. They were on Aldobrandeschi land, but they moved as if they were masters. For Omberto, educated in the pride of his lineage, raised in the chivalric ideal of defending the honor of his lineage, this was an intolerable affront.

The assault was sudden and decisive. The Sienese emissaries found themselves imprisoned within the walls of Campagnatico Castle, hostages of the arrogant count. It was a gesture that respected the ancient code of chivalry—defending one's territory, punishing arrogance—but which failed to take into account the new political reality.

Siena, a rising commune under the banner of liberty (but with an oligarchic government no less predatory than the feudal one), could not allow such an outrage. Three long years passed—three years of growing shadows, of plans hatched in secret, of revenge meditated with relentless patience.

The knight's betrayal and death

1259 marked the end. The Sienese assassins came—not in open battle, as a knight deserved, but in the shadows, armed with the weapon of treachery. Perhaps one of his vassals, perhaps one of his own relatives, opened the gates to the enemies. History doesn't tell the whole story, but it whispers of blades struck from behind, of a knight betrayed in his own land.

Omberto fell at Campagnatico, struck down with the ferocity the Sienese reserved for those who dared challenge them. The rain fell, washing away the spilled blood, flowing fertilely over his beloved Maremma. He had defended his fiefdom as chivalric tradition dictated, but times were changing.

Legend has it that it was the Knights Templar who recovered Omberto's body. His brother William II, the Templar, came with three hooded brothers (who appeared to have no heads, like the fallen knights in the Holy Land) to carry the body to where the brothers of the Order who had passed away "lived." They blessed the place by drawing a circle of holy water around the deceased, to ward off the forces of evil and ensure that the light would always be with him.

Since then, during the nights of Campagnatico, legend has it that a squadron of white knights led by the Templar William can be seen, with Omberto among them, defending secrets and treasures hidden in the Maremma hills.

His sister Folchina inherited Omberto's estate, married as she was to Donusdeo Tolomei. Slowly, inexorably, the castle passed into the hands of Siena—the very Siena that Omberto had dared to challenge. "Once the Lion had fallen," as the poet described it, "the ravenous She-Wolf" of Siena threw herself on the remaining "little lions."

Immortality in the Divine Comedy

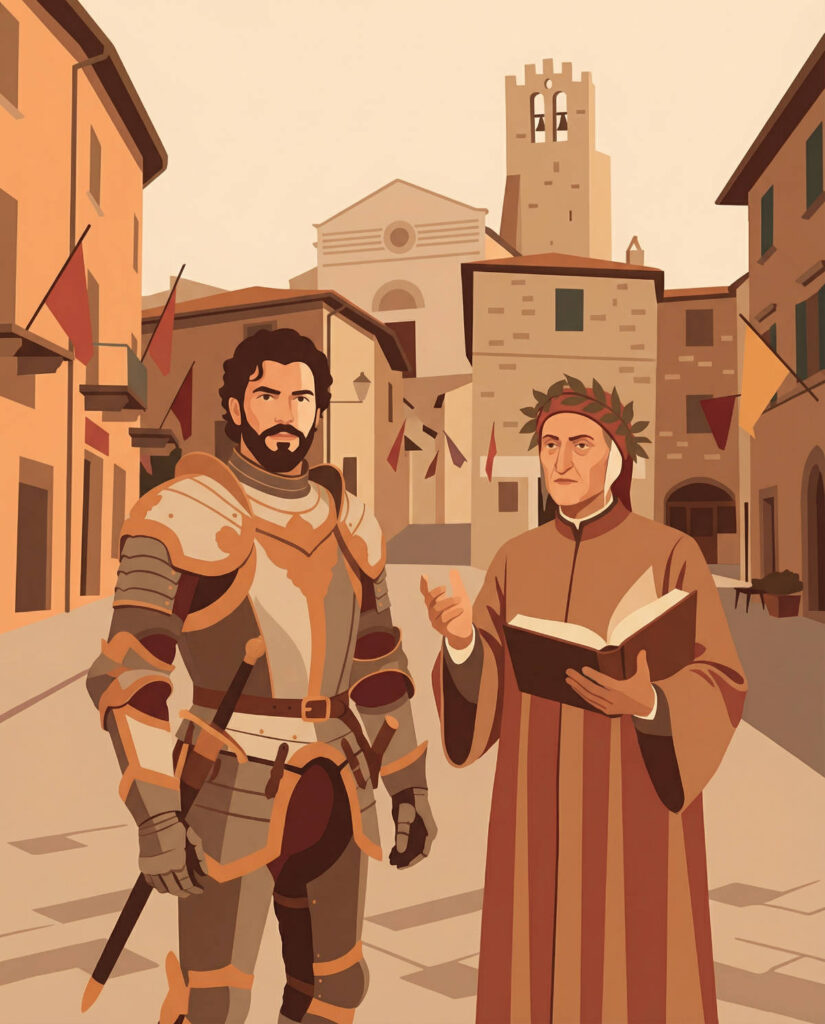

But death was not the end for Omberto Aldobrandeschi. Seventy years later, an exiled Florentine poet would perhaps walk these same lands, listening to the stories still told of the proud count. Dante Alighieri—who had known exile, wounded pride, and unyielding pride—understood Omberto profoundly.

He placed him in the first frame of Purgatory, among the proud, condemned to carry a heavy burden on his shoulders, his face bowed under the weight of his own arrogance. But he did not condemn him harshly: he portrayed him with the complexity of one who sees man beyond sin.

“I was Latin and born of a great Tuscan:

Guiglielmo Aldobrandesco was my father;

I do not know if his name was ever yours.

The ancient blood and the graceful deeds

of my ancestors made me so arrogant,

that, not thinking of our common mother,

I held every man in such disdain,

that I died of it, as the Sienese know,

and every servant in Campagnatico knows it.”

Thus Omberto speaks of himself in Canto XI of Purgatory, confessing with painful clarity that pride that was both his strength and his downfall. He speaks of his ancient blood, of the glorious deeds of his ancestors—that chivalric legacy that the Aldobrandeschi proudly bore.

The flayed lion and the boar

The ancient coat of arms of the Aldobrandeschi of Sovana depicted a flayed lion rampant—a symbol of valor, dominion, noble heroism, fortitude, courage, and magnanimity. The lion was the king of coats of arms, representing the captain who marches to war. The red lion on a gold field was the emblem of a warrior who was all fire in his execution, full of fidelity in his actions.

But there is another animal linked to Omberto's memory: the wild boar. A symbol of courage, of those who overcome the most difficult challenges, the boar was the perfect emblem for a man who lived—like the wild boar—along forgotten valleys, exiled in his own land out of respect for the oath of his chivalric "art."

Legends still remember him: like the wild boar, Omberto spent his last days in the lands he loved, while his enemies feared him. And when he fell, his "art"—that of the knight faithful to his code—must have torn the depths of the souls of traitors like the boar's snout tears the earth.

Echoes in the present

Today, in Piazza Dante Alighieri in Campagnatico, a plaque commemorates that man and that fate. Visitors pause, read, and gaze up at the ancient stones. Perhaps they wonder what Omberto was really like: a ruthless tyrant or a noble defender of his own rights? A victim of Sienese arrogance or the architect of his own downfall?

Today, in Piazza Dante Alighieri in Campagnatico, a plaque commemorates that man and that fate. Visitors pause, read, and gaze up at the ancient stones. Perhaps they wonder what Omberto was really like: a ruthless tyrant or a noble defender of his own rights? A victim of Sienese arrogance or the architect of his own downfall?

A chronicler wrote: “Siena deserves particular mention, in its dishonorable conquest of the Maremma, where it ruined, destroyed, and annihilated everything; many populous places were razed to the ground by it, never to rise again, and today they are barely pointed out to the astonished traveler from the remaining stone piles.”

The Aldobrandeschi—those princes of Maremma who owned a castle for every day of the year, who had given the Church a Pope (according to some, Gregory VII was of their lineage), who had fought in the Holy Land with the Templars—were systematically wiped out. Their castles were destroyed, their most beautiful and strongest trees uprooted, their memory obscured.

But Omberto survived. Not in lost possessions, not in dissolved power, but in the immortal words of a poet who could see beyond the propaganda of the victors, capturing the eternal essence of the human soul.

The landscape witness

The hills of Campagnatico haven't changed all that much. They still gently roll toward the horizon, the Mediterranean forests still embrace them with their emerald green, the fields still alternate in that multicolored checkerboard of wheat and plowed earth that even Omberto must have seen.

The Ombrone River flows as it did then, a placid witness to human events. And when the wind blows through the cypress trees, it seems as if we hear ancient whispers, memories of a time when these places were the scene of struggle, passion, and betrayal.

The allure of the ancient chivalric ideal

There is something profoundly human—and at the same time, titanically noble—in the story of Omberto Aldobrandeschi. Wasn't his arrogance the same pride still required today of those who defend what they believe in? His refusal to bow, his pride in his name and lineage, his fidelity to a code of honor that demanded fighting for justice and tradition—aren't these values that endure through the centuries?

He embodied that chivalry that the modern world has forgotten, where the armed knight was the defender of hierarchy, law, and religion—a protector rather than a blind servant. An ideal that Saint Bernard had celebrated for the Templars: "Impavidus miles, who dresses his body in iron and his soul in the armor of faith, fears neither demons nor men, nor death itself."

Omberto knew the feudal dream was fading. He foresaw the rise of the Communes with their predatory oligarchic governments. He understood that overwhelming forces were about to overwhelm his world. Yet he did not yield. He remained faithful to the oath of his chivalric "art," even knowing it would lead to his ruin—and with him, all his consorts.

This was his true greatness, more than his pride: his undaunted perseverance in the face of the inevitable, his refusal to betray himself even when it would have been more prudent to do so.

The invitation of memory

Come to Campagnatico, seek out that harmonious square where every stone seems to speak. Read Dante's tercet engraved on the stele. Imagine the count who once ruled these lands—not as a tyrant, but as a knight faithful to an ideal the world was losing.

Stroll through the hills that Omberto defended with his life. Listen to the wind in the cypress trees: perhaps it still carries the echo of that indomitable pride, that unwavering loyalty to his values. And if on full moon nights you think you see white knights led by William the Templar, don't be surprised: the legend has deeper roots than the history written by the victors.

Remember that history is not just made up of dates and battles, but of people who chose—with their dreams, their weaknesses, their indomitable passions—to remain true to themselves until the end.

Omberto Aldobrandeschi has been dust for centuries, his castles are ruins, his immense fiefdom has been erased. But his name lives on, transformed into an eternal symbol by a poet who understood that true greatness lies not in victory, but in remaining faithful to one's "art"—no matter the cost.

And when you wonder if it's still worth defending ideals the world considers lost, think of Omberto. Consider that seven hundred years after his death, we are still here to tell his story, while the names of the assassins who killed him are lost in oblivion.

This, perhaps, is the only true way to escape death: to become a legend, to transform oneself into a symbol, to live every time someone stops to remember that once, in this land, there were men who preferred to die standing rather than live on their knees.